As the title reveals, and as my previous entry confirms, I spent several weeks in Japan earlier this month for my birthday. As well as visiting the Bank of Japan’s currency museum (see the last post which is dedicated to it), I also had a chance to visit some coin sellers in the Tokyo area. It was visiting these sellers which allowed me to acquire items which normally are difficult to find here in the UK (avoiding searching the internet of course), and usually are significantly more expensive.

I managed to acquire these coins in a varied hodge-podge of places. The coins in the top left corner acquired in the more unusual place. Of course, it goes without saying that visiting Japan and not acquiring a 100 mon coin (bottom left) is practically impossible for a collector. This is not the first I have gotten, as my update back in December showed. However, seeing it for sale in Akihabara of all places, and at a significantly low cost meant it was an opportunity I couldn’t pass up.

So I will first start discussing the coins to the right of the picture. At the top are five 4 Mon coins dating from the middle to late 18th century. A design influenced heavily by the Chinese, it was during this period that Japan declared that Chinese money could no longer be used as legal tender (a practice which had been going on for a fair number of centuries prior to this decision). This was due in part to the large influx of Chinese copper coins disrupting markets in Eastern Japan resorting many Japanese traders to using rice for transactions rather than coins themselves. After 1670, when the use of the old Japanese and Chinese coins became prohibited, many traders instead sold them overseas to make a profit. Vietnam was the main trading hub for these old coins, which resorted in Japanese mon coins becoming the de facto currency of the country due to the large influx of them. This stopped in 1715, when the Japanese Shogunate banned copper from leaving the country.

Below the mon coins is a solid silver rectangular 1 Bu coin, Ichibu-gin in Japanese. Dating from the dying days of the Tokugawa Shogunate (1853-1865). During this period the Shogunate had ruled Japan for roughly 700 years, but by the early 19th century, it was starting to show it’s weaknesses. Handling of several famines during the previous century had not gained it any popularity, and new ideas spreading from the West caused some dissent amongst the peasant population. The situation was further exacerbated by unfavourable demands placed on Japan by the encroaching Western powers. This is heavily characterised by the trade treaties first bargained in the US’s favour by the Perry Expedition in 1853. The Shogunate fell in 1867 when the Shogun Tokugawa Yoshinobu tendered his resignation to the Emperor and stepped down as Shogun. The following year the Emperor Meiji officially ended the Shogunate and after a brief civil war (Boshin War 1868-9) against the remnants of those who wanted the Shogunate to keep power, reclaimed it for the Imperial throne. The return of the Emperor to power in 1868 is known as the Meiji restoration.

The coins in the top left corner I acquired in one of the least likely of places. Again they were found in Akihabara, but this time they were in one of the many Gatchapon machines dotted around the district. Gatchapons are small machines containing pods (or eggs as we call them here in the UK), which for a small nominal sum you receive a random item from those displayed on the front of the machine. Seeing one dedicated to old Japanese coins and banknotes I couldn’t resist having a try. It also allowed me to get rid of some of the change out of my pocket. Some of the items on offer ranged from small iron or copper coins up to old demonitised banknotes. From what I could tell from the picture on the front of the machine, all dated from the early 20th century. The coins I got were a couple of copper Sen dating from the 1910’s and a 10 sen tin-zinc alloy coin dating from 1944. Overall, not worth the change I put into the machine, but honestly the fun and novelty of it all mitigated any financial loss I felt about it.

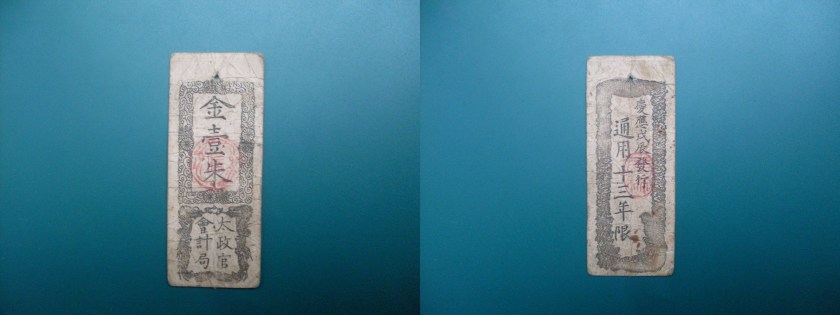

Finally, the last thing I acquired whilst in Japan was this banknote called a Hansatsu. I will freely admit, I had no idea that these things existed until I visited the currency museum in Tokyo. They date from the late 17th century well until the Meiji restoration in 1868 when the Emperor started to issue the first national Japanese banknote called the Dajoukansatsu. Hansatsu notes are very similar to the German notgeld of the early 20th century in that they often could only be used in the region (Han) they were printed in, as well as not being official state issued currency. Most of them had equivalent values equal to metal coinage circulating Japan at the time, but some were also priced in the value of commodities like rice and fish. Some of the larger Hansatsu feature depictions of a large man, who is Daikokuten, one of the seven Gods of fortune from the Buddhist faith. He is often seen sat astride two rice bales due to his close connections with agriculture. He was also associated with weath, happiness and good fortune leading him to become a favourite deity throughout Japan.

One thought on “Collection update – Japan Special”