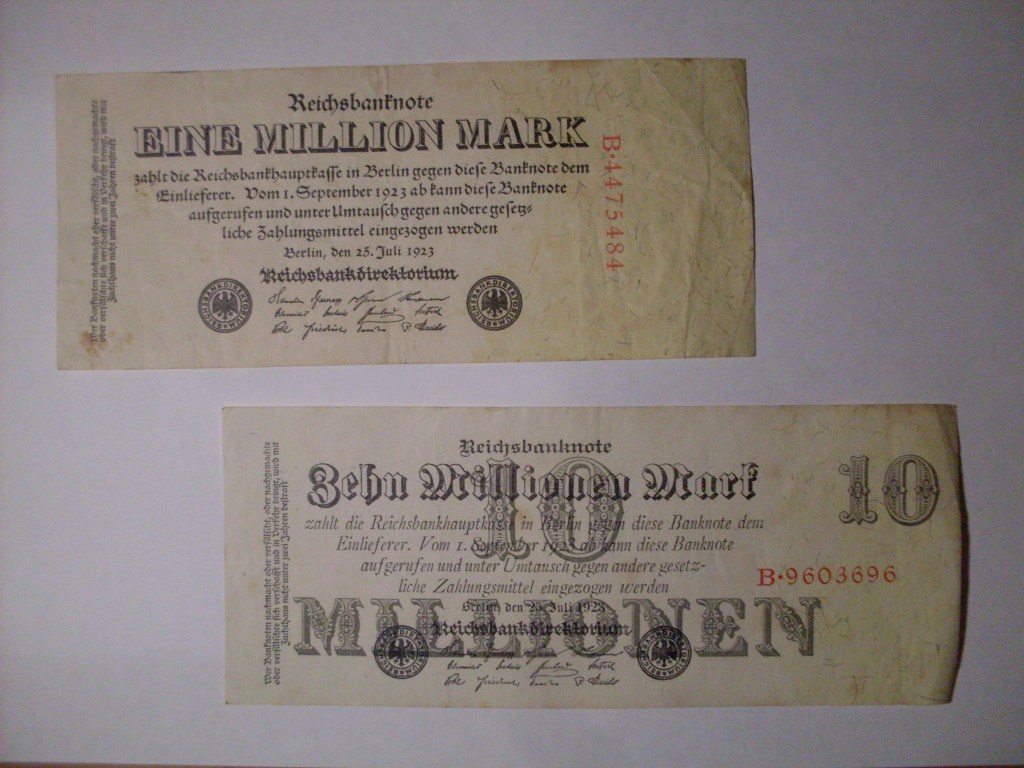

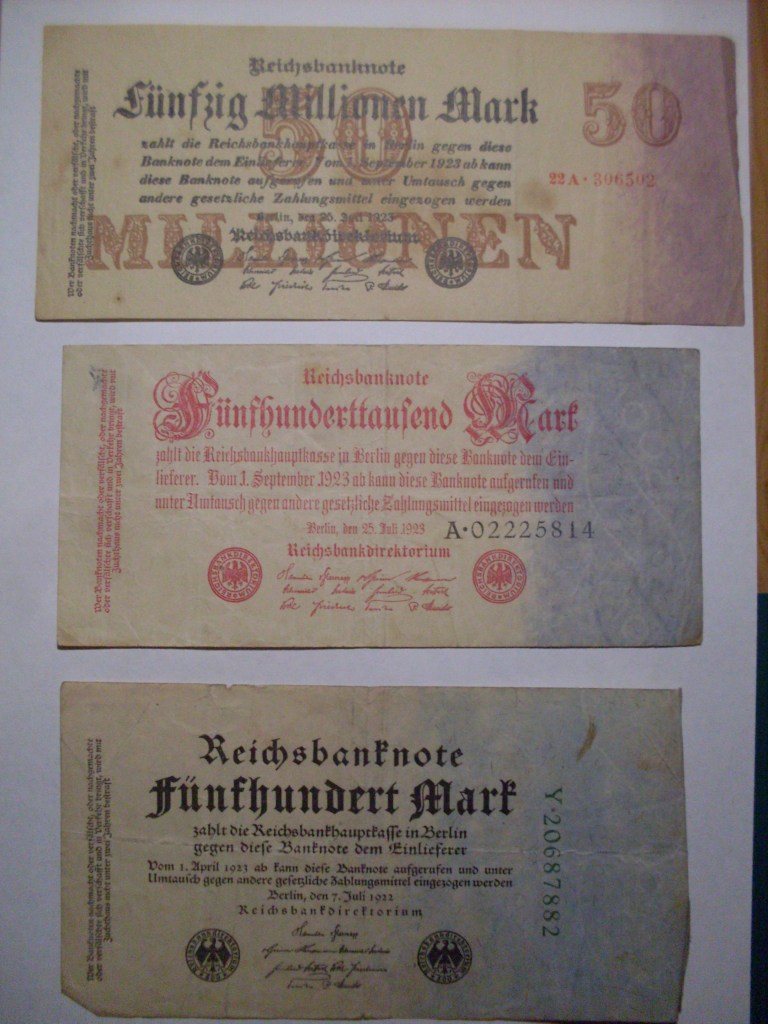

For September we return to Germany to look at some banknotes from a period in the country’s history which is heavily studied. Especially by those learning history here in the UK.

This period defined the inter-war years for Germany. It weakened the new Weimar Republic which emerged after the horrors of WWI and the overthrow of the Kaiser. This brief period of hyperinflation would set the scene and help sow the seeds for a much darker regime to follow.

When Germany lost the war in 1918, it was saddled with massive debts due to the increased borrowing the Kaiser and his government undertook to fund it’s effort during the conflict. Exacerbated further by the harsh conditions imposed upon Germany by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. Despite some economic relief provided by the Young Plan, the debt burden was worsened by the printing of money with no economic resources to back it. Reparations as set out in the Versailles Treaty accelerated a decline in the German Mark as more money was printed to meet these obligations. By the end of 1919 it would take 48M to equal just $1 in value.

By the time Germany was to meet it’s first reparation payment in June 1921, the value of the Mark had slipped further with 330M now needed to just meet $1. As the reparations had to be paid in hard currency rather than the slowly falling ‘Papiermark’ (Paper money), the German government began to exchange marks for foreign currency at any value. This action would further destabilise the currency as it was seen by many as the German government selling their own currency in preference for foreign. Thus weakening the trust in it’s value.

1922 would mark the beginning of the rapid decline in the value of the German currency. By June of that year a conference organised by investment banker J.P Morgan tried to solve the situation and organise reparation repayments. Since no workable solution was able to be found, the inflation would continue to skyrocket. By the years end, 7200M would equal $1. The strategy employed by Germany was to mass print new banknotes in order to buy foreign currency to pay the reparations. This of course destabilised the economy greatly, with much of the banknotes now not being worth the paper they were printed on.

By 1923, Germany was no longer able to make it’s reparation payments and the French would respond by occupying the Ruhr valley, Germany’s main industrial region. The German government would encourage the workers of the region to adopt a policy of passive resistance by not helping the invading French in any way. The workers though would need to be supported financially during this ‘strike’ against the French occupation. Thus leading to more banknotes being printed.

By the end of 1923, new plans were proposed by the central German bank to tackle the crumbling economy and rein in the continual rising prices. A new currency was to be introduced in Germany, the Rentenmark, back by bonds indexed to the physical value of gold. In parallel to this, a new bank was set up to control this currency called the Rentenbank. The new bank would refuse credit to the government and currency speculators in an attempt to create value for the new currency.

Over the course of 1924, the new Rentenmark would be expanded in scale until it would be formally adopted as the de facto currency in Germany in August of that year. By the time of it’s formal adoption the value of the currency would be 4.2 rentenmarks to a single dollar. Conversion values between the old Mark and the new Rentenmark would be set at 1-trillion marks to 1 rentenmark.

Overall, hyperinflation in Germany would reach it’s peak around November 1923 with the average price of a loaf of bread at the time coming to 200,000,000,000 Marks. The economy would stabilise and prices would return to normal relatively quickly with the introduction of the Rentenmark. Despite being separate events, many Germans would conflate the hyperinflation of the 1920’s along with the Great Depression and see both together as one large economic crisis.