This month I had some long-awaited time off work, and due to the current pandemic hitting everywhere I did some day trips to other places here within the UK (A chance to see somewhere different from the small town I live in). One of these places was the city of York. A place I haven’t visited in about 10 years, and it has always been a charming city to visit for those who love history.

Whilst wandering the streets of York I came across an antique centre a stones throw away from the minster, and with time to kill before my train, I decided to have a look around.

Whilst perusing the cabinets I was more than tempted by the coins they had on offer, however in the last room at the back of the building I stumbled across what this month’s blog post will be about. At first, I dismissed it, but I found as I kept looking through the cabinets I was constantly drawn back to this item. It is nothing special or unique, but I found that by the end of the day I just had to have it.

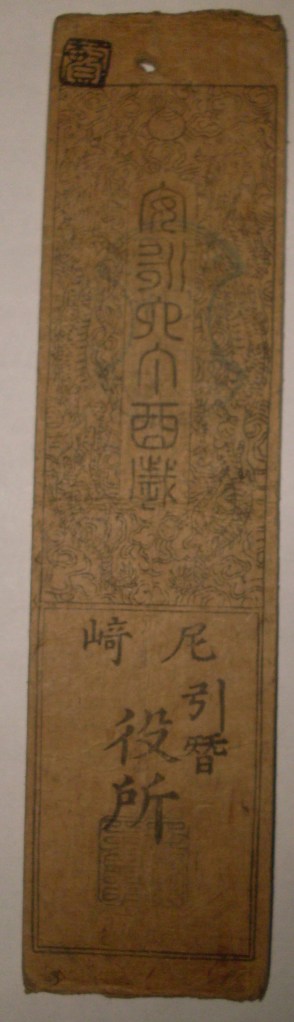

The item in question, although not a coin itself, is related to coins and money. A little drab, and the years have not been too kind, but this early Showa Era (1926 – 1989) Japanese money box had a charm of it’s own.

The box is made of metal and has a dial and key type lock. Both dials have to be set to the correct combination and the lock has to be opened by the key before the lid is able to be opened by the knob found just above the keyhole.

Made between 1926-1936, this moneybox was manufactured under the Alps brand in Tokyo. Other such brands exist at the time showing similar designs and lock mechanisms. Brands such as Mitsuba, Star, Mitsuwa, High Class, and Dial also look very similar to the Alps brand I purchased.

The word Chokinbako (貯金箱) can be translated into moneybox, money bank, or loosely for Western tastes “Piggy-bank.” So it can be assumed this was an item to save up money.

In the West, the oldest money box which has been discovered dates from the 2nd century BC at the site of the Greek colony of Priene in Asia Minor. Money boxes have also been excavated at Pompeii and Herculaneum, and soon make an appearance across much of the late Roman Empire. It is believed that in the west the popularity of the ‘piggy-bank’ originates in Germany where pigs were revered as a symbol of good luck. The oldest German piggy-bank dates from the 13th century and was discovered during construction work in Thuringia.

In Asia, we can find the earliest known pig shaped container dating from the 12th century. It was discovered on the island of Java in Indonesia. Further pig shaped money boxes were also found in archaeological excavations in Trowulan, a village in the province of East Java and is believed to be the possible site of the capital of the ancient Majapahit Empire.

The term “piggy-bank” itself is in dispute with the earliest known use dating from the 1940’s. The earliest known use of “pig-bank” in English dates from 1903, which describes them as a Mexican souvenir. In Mexico piggy-banks are called ‘alcancia’ which originates from Andalusian Arabic.