Finishing off a small series of blog posts regarding my recent visit to Japan, I would like to close discussing my experiences with the sellers I encountered whilst visiting there. I was hoping to visit some traders whilst in Kyoto, however due to ill weather and conflicting plans, I never had the chance, so this blog post will mainly be dealing with those sellers I interacted with in Tokyo.

The first seller I visited was Ginza Coins (website in Japanese), funnily enough in the Ginza locale in Tokyo, south of the main train station. I was surprised with the location of this shop, as it was located within a shopping centre (something which is deemed very unusual in the UK), and didn’t seem out of place at all with the expensive clothing boutiques surrounding it. Many of the coins on display were behind glass cabinets, with some cheap lucky dip bins on top. Most were Japanese, but there were some proof sets from the US and Australia for sale as well. I think I remember seeing the odd proof Chinese coin too. The prices themselves were not extortionate, although a little above actual catalogue price (I know most shops add extra for overheads etc). What struck me the most was the fact that after asking to view a tray of coins the staff member quietly went back to her work and left me alone. This was a pleasure in itself. So often whilst perusing coins I have had staff members hovering nearby adding a subtle layer of pressure to speed up the process. Despite being a small-ish counter top in a shopping centre I was fully relaxed and at ease. I am not sure if this was regular Japanese business practice, or absolute trust in that I wouldn’t run away with the goods. Either way colour me impressed. Although….it could have been a clever sales tactic as I did buy more than I intended…

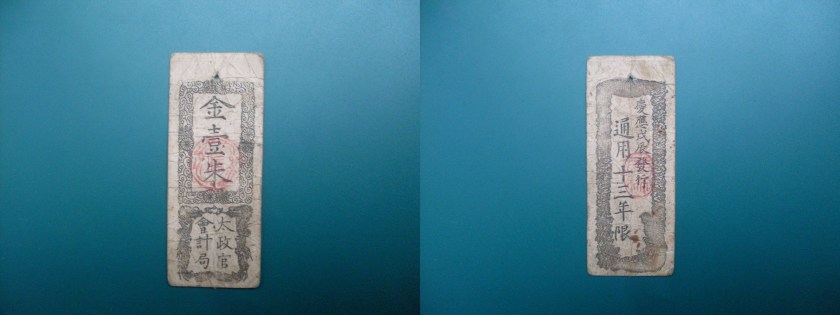

I had a somewhat similar experience at the next seller I visited. Although further afield from downtown Tokyo, the antique shop Wasendo in Asakusa was definitely worth the walk. Located in a small shopping arcade close to Senso-ji temple, it too had a casual atmosphere about it. Items on offer ranged from the numismatic to the philately, as well as numerous postcards and other items accustomed to the antique. Upon entering I was given a cheerful hello by the owner and then left to my own devices. The shop is not very big, similar in size to Ginza Coins, but certainly has more on show and is a feast for the eyes. Many of the items I bought during my visit were mixed in with most other items for sale, so it had an air of a treasure hunt about it. Similarly to Ginza Coins, when asked to see if I could examine a tray of coins in one of the cabinets I was left alone without residual pressure from the shop owner to hurry up.

Items on offer were a lot more varied from those at Ginza Coins, as there were coins and banknotes stretching worldwide, so I had the feeling of being like a kid in a candy store more than I should have. Prices were not far different from what I paid in Ginza either, but the added variety meant I had to be more choosy with my purchases. I did end up going back after leaving as I spotted a large collection of notgeld for sale in the glass cabinet outside…. I am sure the owner thought I couldn’t stay away.

Overall, my experiences of the sellers in Tokyo was very positive, the only downside and a piece of advice I could give you is to know what you are looking for if you are searching for something specific. Like most Japanese, communicating in English was very difficult, so resorting to gesticulating and basic phrases was a common occurrence. Although they were extremely patient with me. Furthermore, everything written down is in Japanese, so unless you know exactly what you are looking at, don’t expect any explanations from the staff, as again English is not really catered to.