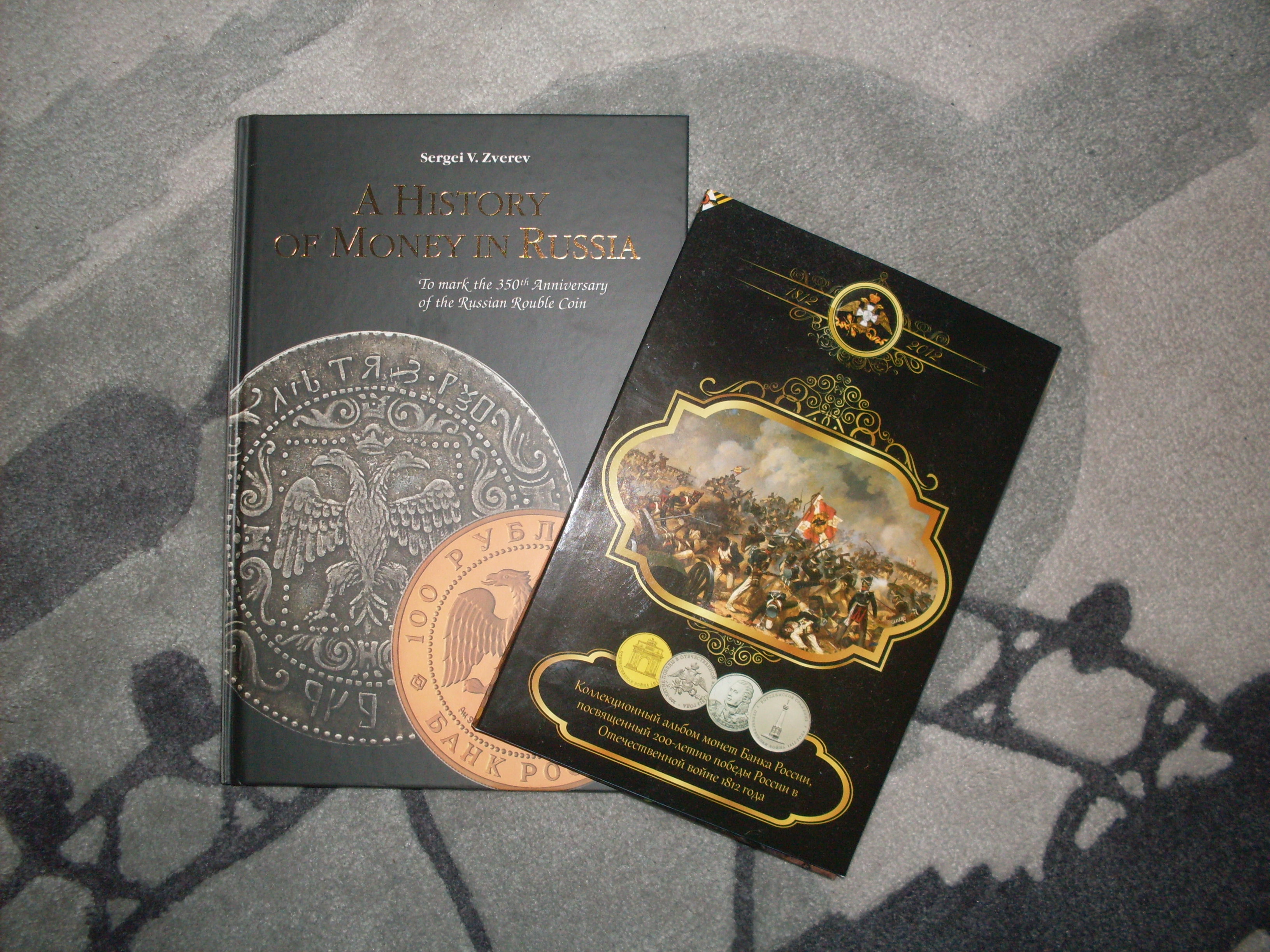

We are returning to Russia again this month and with something slightly different from the norm. Now in the picture above we see a perfect copper replica of the Russian half-poltinnik which originally was minted in silver during the reign of Czar Alexei Mikhailovich (1645-1676). However, it is not a forgery. It is actually a coin weight used to measure the quality of the afore-mentioned half-poltinnik.

Coin weights themselves were often made of a variety of materials, ranging from metals to glass. Most often bore an inscription of the coin they were supposed to represent, or were straight up copies like the one I have acquired.

Not limited to the medieval period, the history of coin weights date back to ancient Ptolemaic and Byzantine times, and there is significant evidence that they were also used in ancient China.

(The inscription reads: “Czar and Grand Prince Feodor Alexeyevich of all Rus”)

This coin weight was minted during a period of monetary reform in Russia. In the middle of the 17th century there was signs of a strengthening of monetary currency, growth of the Russian internal market, reinforcement of Russian state power, and the annexation of the Ukraine in 1654 made monetary reform a necessity. These reforms were carried out in 1654 with the aim of introducing a new set of small and large denomination coins to replace the silver wire kopecks previously in circulation. Inspiration was drawn from Western currencies, with the new silver Rouble taking it’s ideas from the West European thaler. Many of the new silver roubles were made by simply counter-marking existing thalers (or other coins of the same weight and value). Half-poltinniks were made by simply cutting these Western thalers into quarters.

However, there was much public mistrust over this new coinage due in part to unfamiliarity and the way the coins were issued to the population. Thus, just a year later in 1655, the reforms were abandoned. This was shortly followed by a mass striking of new copper coins using the old denga and kopeck system, with many of the designs modelled on the old familiar silver wire kopecks.

Ironically the mass striking of the new coins led to inflation quite quickly, and with the sharp rising of prices, the economy in disruption, the Copper Riot of 1662 happened in Moscow. This led to the eventual nullification of all copper coins in 1663 and would not see a reintroduction until much later.